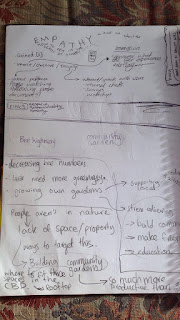

Research and idea generation

Fist class idea generation

Briars further Idea Development:

Annabelles Further Research:

Healthy places, healthy lives: urban environments and wellbeing

" Cities and towns also influence health in a way that goes far beyond the presence of health services in these areas (see Figure 1). The way urban areas are planned and laid out – known as urban form – shapes people’s life choices and has a strong bearing on health outcomes. Urban form affects where we live, how we travel to work or school, how clean our air and water are, whether we are active, and what shops or other facilities we use. Appropriate planning of urban areas has the potential to help New Zealanders live healthier lives in a range of ways. For instance, planning can provide opportunities for physical activity and social interaction, and access to employment, health services and green space.

In high-income countries such as New Zealand, advances in engineering during the past 50 years have reduced physical activity in daily urban life. People drive to work, school or the shops, work is more sedentary than it was for people in previous generations, and recreation is also increasingly passive.6 Many of New Zealand’s urban areas, built over the past 50 years in response to population growth, were planned around these advances in engineering. Such neighbourhoods often have poorly connected street networks (for example, cul-de-sacs rather than grid-like streets) and low-density housing that is beyond walking distance to shops, workplaces and public transport.7 International and New Zealand research suggests that the way we have been designing and planning our cities over recent decades is leading to some unintended negative consequences for health. Planned primarily around cars, these neighbourhoods are not conducive to physical activity for either recreation or active transport. In the resulting environments, there are fewer opportunities for social interaction, more motor vehicle emissions contributing to poorer air quality

and greater risk of road traffic injuries. The prevailing type of urban form also has negative consequences in terms of the environment and climate change and adds to New Zealand’s ‘carbon footprint’ "

URBAN ENVIRONMENTS AND HEALTH

Today, in the early 21st century, 87% of New Zealanders reside in cities. The health issues that confront modern New Zealand cities are in some respects very different from their Victorian counterparts, but the need for a concerted and integrated response from planning, urban design and public health are key to securing an urban form the meets the new challenges. These new challenges are less to do with basic sanitation and disease control (although these remain relevant), and are more to do with the focus of modern planning where the private automobile is its centrepiece, and the health impacts and social dislocation that accompanies it. Modern public health advocates are particularly concerned with the impact of transport, housing development and land use planning on people‟s lifestyles and opportunities to maintain health throughout the life course (Public Health Advisory Committee 2008a). This has brought with it a widening of the public health sphere of focus from communicable diseases, such as cholera and tuberculosis, to non-communicable diseases such as heart disease and diabetes, and important health-related risk factors such as alcohol and safety. A fundamental challenge is to build, re-build or retro-fit urban environments that counter the direction of 40 years of urban planning which have treated cars and public interest as one and the same. Undoubtedly, the car has increased the mobility of people and supported access to services and amenities across significant distances, but the caroriented basis of urban planning has at the same time eroded the ability for people to live actively in their local environments. For many urban residents, accessing local services and amenities either necessitates private transport, or actively discourages active modes. The reliance on private transport has also brought with it rising levels of air pollutants with attendant health impacts (Macmillan & Woodward 2008). Furthermore, urban planning has a key role to play in improving safety across many PAGE | 4 domains, not just in terms of traffic but also in the experience of urban environments that give rise to perceived or actual safety concerns.

Warning: living in a city could seriously damage your health

Another antidote to noise, particulates and greyness is both delightful and affordable: trees. For humans, urban trees provide not just aesthetic pleasure but health benefits. Trees soak up air pollution, create cooling and provide a brain-tingling array of colours, textures and scents. The birds they shelter provide us with birdsong, which in turn is linked to feelings of wellbeing.

Consider the example of Toronto, Canada. The city values its 10m trees at C$7bn (£4.3bn). A 2015 study there showed the higher a neighbourhood’s tree density, the lower the incidence of heart and metabolic disease, and estimated that the health boost to those living on blocks with 11 more trees than average was equivalent to a C$20,000 gain in median income.

Urban Sanity: Understanding Urban Mental Health Impacts and How to Create Saner, Happier Cities

Urbanization Mental Health Impacts

Increased Risk

|

Reduced Risks

|

|

|

This study identified the following mechanisms through which urbanization can impact mental health:

- Concentrated mental illness risks.

- Substance abuse.

- Social isolation and loneliness.

- Noise and light pollution

- Toxic pollution.

- Excessive stimulation and stress.

- Crime.

- Crowding.

- Economic stress.

- Transport conditions.

- Inadequate access to nature.

This research suggests that the following urban policies and design strategies can help create saner and happier cities:

- Targeted social service.

- Affordability.

- Independent mobility.

- Pro-social places.

- Community safety.

- Design for physical activity.

- Pollution reductions.

- Greenspace.

How Parks Affect Mental Health, Backed By Science

1. Parks Lower Stress

Even a short walk through a park can have a positive impact on your mental health. Finnish researchers examined Cortisol(a hormone released in response to stress) levels of 77 in three parts of Helsinki—the city centre and two parks. According to the findings published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology, participants felt less stressed and more creative in the park environments than in the city centre.

2. Parks Lower Depression

Spending time in green environments can relieve not only anxiety and stress, but also sadness and depression. In a Dutch study on anxiety, the annual prevalence of physician-classified depression in areas containing 10 percent green space was 32 per 1,000; in areas containing 90 percent, it was 24 per 1,000. Less access to nature is linked to exacerbated attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, more sadness and higher rates of clinical depression.

3. Parks Increase Happiness

Better yet, when you move to a greener neighbourhood, the mental health benefits are long term. The American Chemical Society’sEnvironmental Science & Technology journal did a study of over 1, 000 UK residents and found that those who moved to greener neighbourhoods still felt the mental health benefits three years later. In contrast, the happiness increase from a pay raise or promotion usually lasts only six months.

Urban green spaces in vacant lots can reduce depression and anxiety

They found that people living within a quarter of a mile radius of greened lots had a 41.5% decrease in feelings of depression compared to those who lived near the lots that had not been cleaned. Those living near green lots also experienced a nearly 63% decrease in self-reported poor mental health compared to those living near lots that received no intervention.

Comments

Post a Comment